Bone and Joint infections

Prosthetic Joint Infection

It is one of the most common complications associated with any type of prosthesis

LESÕES

DO JOELHO

INFEÇÕES OSTEOARTICULARES

Bone and Joint infections

Prosthetic Joint Infection

What is a Prosthetic Joint Infection?

Although it is straightforward in theory to define a prosthetic joint infection (often termed "rejection") as a failure caused by the presence of bacteria at the prosthesis-bone interface, in clinical practice, it can be extremely challenging to be certain of its presence or absence.

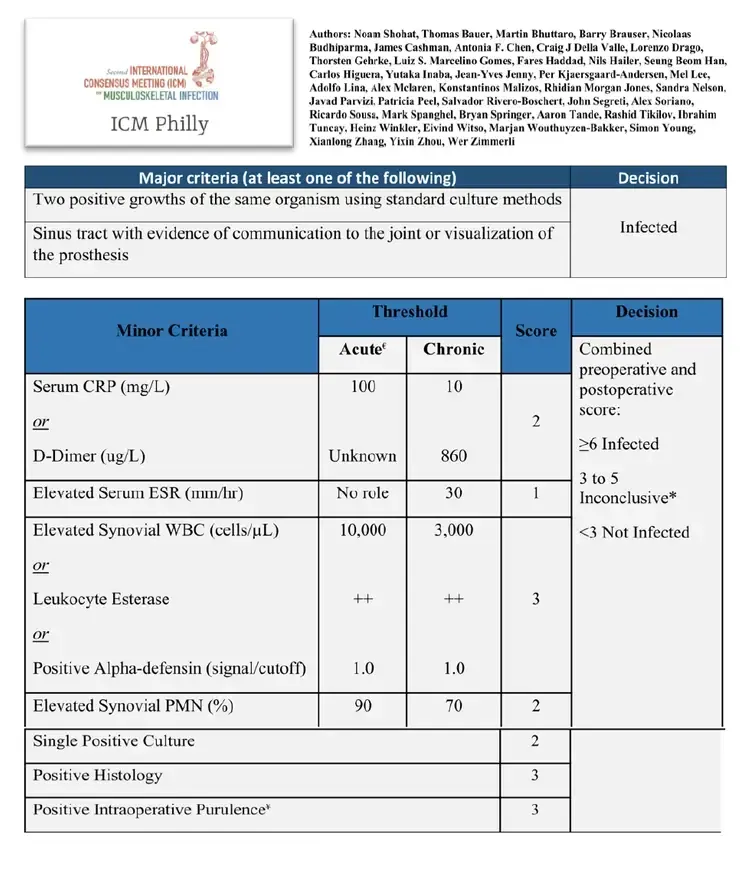

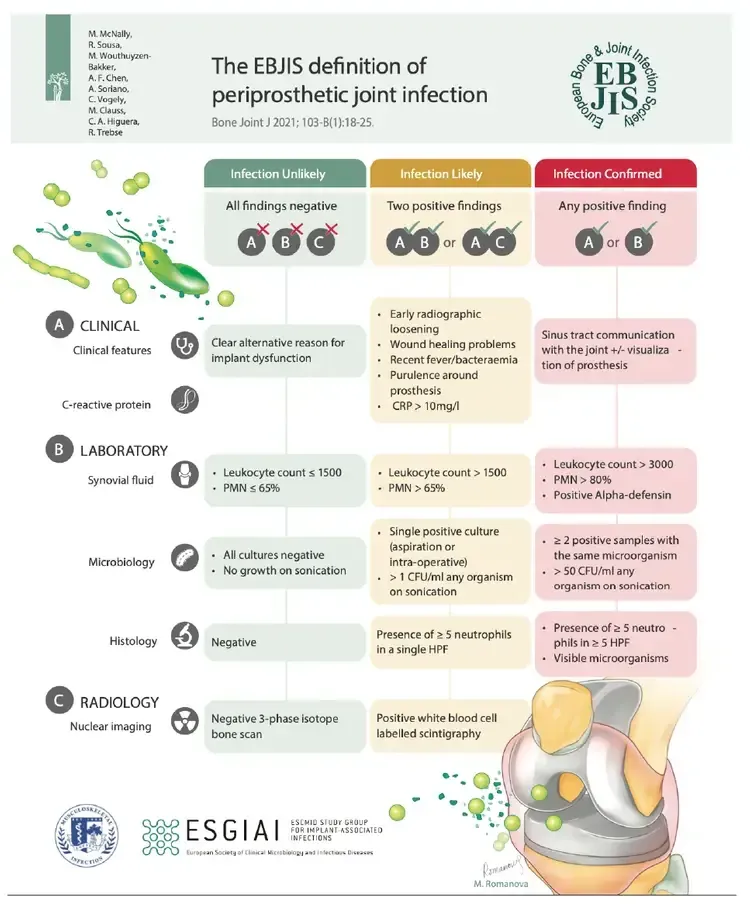

This difficulty is underscored by the existence of various definitions in international literature, with the two most recent being from the International Consensus Meeting (ICM) in Philadelphia 2018 and the European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS) 2020, co-authored by Prof. Dr. Ricardo Sousa himself. (fig1 and fig2)

CausEs

In most cases, infections arise from bacterial contamination during the original surgery. Consequently, most infections are diagnosed within the first few years after the prosthesis placement.

Despite all preventive efforts, the reality is that there is a small but persistent global prevalence of infections, around 1-2%.

Certain risk factors, such as obesity, diabetes, renal insufficiency, and immunosuppression, can increase this risk.

Symptoms

Typically, a prosthetic joint infection does not present with overt signs of florid infection such as pus and fever. Instead, it is more commonly characterized by chronic pain, potentially accompanied by symptoms such as swelling and/or stiffness.

This occurs because bacteria on the prosthesis surface form a biofilm, which protects them from the body's immune system and antibiotics, leading to a persistent but localized inflammatory response that evades traditional clinical and laboratory criteria for infection assessment.

Diagnosis

Preoperatively, a mere clinical and radiographic evaluation is insufficient to rule out prosthesis infection. Except in cases where a cutaneous fistula with drainage clearly indicates infection, the physical examination can be extremely nonspecific and variable, and may even appear completely normal.

The initial assessment should therefore include both clinical and laboratory examinations to identify:

1) Presence of risk factors for infection, such as comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, obesity, immunosuppression) or surgical history (previous surgeries/revision surgeries, difficulties in healing/prolonged postoperative drainage).

2) Chronology of pain, as earlier failures post-surgery typically indicate a higher likelihood of infection.

3) Presence of inflammatory markers like erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP).

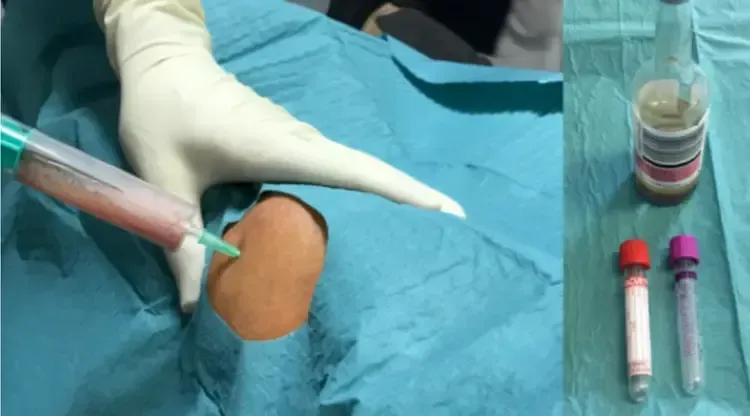

If all these parameters are negative, the likelihood of infection is extremely low, and other causes of pain should be thoroughly investigated. If suspicion persists, the best preoperative diagnostic step is to collect synovial fluid for analysis. In the knee, this can be performed simply on an outpatient basis; for other joints (e.g., hip or shoulder), the procedure might require ultrasound or fluoroscopy support in the operating room (fig 4)

The fluid should be tested not only for direct detection of bacteria via microbiological study but also for markers that indicate the body’s response to potential bacterial presence. This is crucial as biofilm-associated infections may not release free bacteria into the synovial fluid, resulting in a negative microbiological test despite the presence of infection.

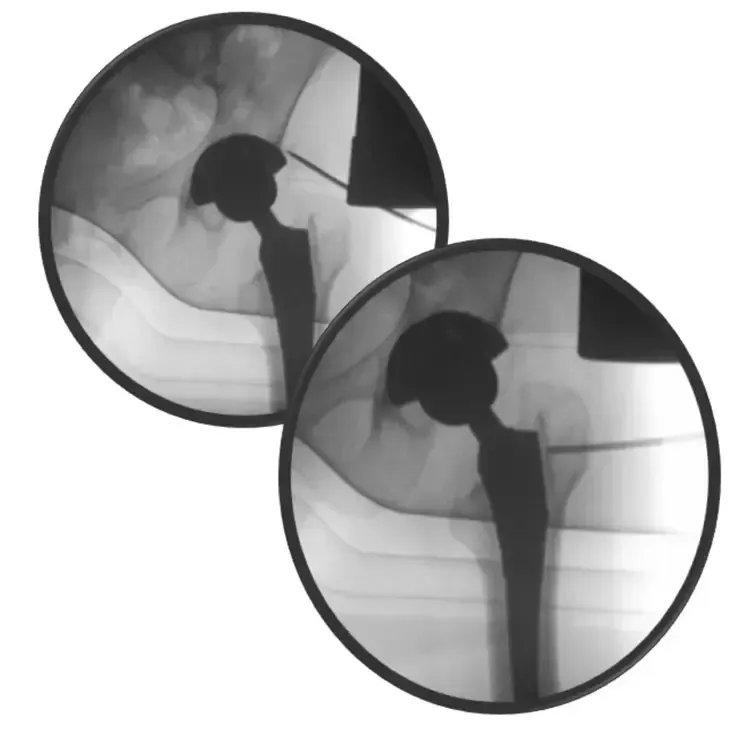

In cases where fluid collection is not feasible (more common in joints other than the knee), further tests such as percutaneous biopsies may be necessary. These must be performed in a strictly sterile environment, typically in the operating room with fluoroscopy support (fig 5).

Definitive Diagnosis

Even with optimized preoperative evaluation, a definitive diagnosis—confirming the presence of infection, identifying the responsible bacteria, and determining their antibiotic sensitivities—is often only achieved during revision surgery of the prosthesis.

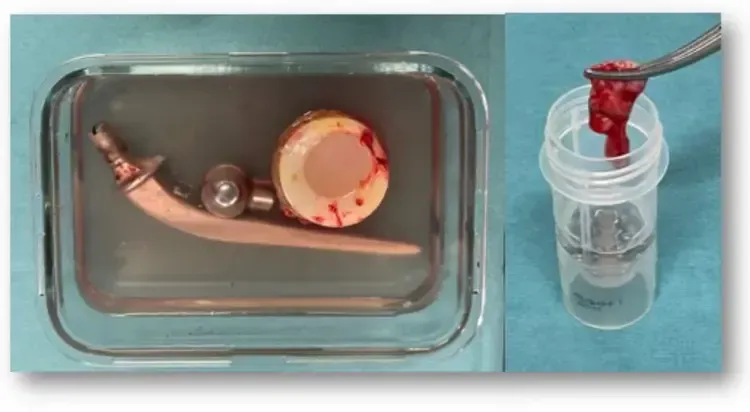

The implant should also be examined for biofilm on its surface through a process called sonication. Effective diagnosis requires close coordination between the surgeon and the laboratory. Besides microbiological analysis, histological examination can also assist in confirming the presence or absence of infection, though it does not specify which bacteria are involved or the most effective antibiotics.

Opções de tratamento

In the vast majority of cases, the treatment of a prosthetic joint infection involves some form of surgical intervention, accompanied by antibiotics targeted at the specific bacteria identified.

This surgical intervention might consist of a simple surgical debridement if the infection occurs in an acute phase, or a revision surgery if the infection is diagnosed in a chronic phase.

Traditionally, a two-stage revision is employed: initially, the infected prosthesis is removed, and a spacer loaded with high doses of antibiotics is inserted to maintain joint function and combat the infection. Subsequently, once the infection has been eradicated, a second surgery is conducted to implant a new prosthesis.

With advancements and expanding expertise in this field, it has recently become feasible to significantly shorten the interval between the two surgeries. In select cases, it may even be possible to manage the condition with a single-stage revision.

Fracture

Related Infection

Fracture-related infection is now the most common type of bone infection.

Click to find out more information

Copyright © 2026 Ricardo Sousa Ortopedia All rights reserved

Copyright © 2026 Ricardo Sousa Ortopedia

All rights reserved

Powered by Pointfull.